What and why is stakeholder participation needed? I How is stakeholder participation used to contribute to a sustainable bioeconomy? I What are the limitations? I Summary of key results

Besides technical and economic factors, societal factors, interests, perceptions, mentalities, narratives and ideologies - beyond solely ‘acceptance’ - will mainly determine the further development of the bioeconomy [1]. These may be evaluated using the tools of stakeholder participation.

What and why is stakeholder participation needed?

Stakeholder participation includes all the ways stakeholders are involved (surveys, workshops, etc.) in a task such as policy making or research. Systematic stakeholder participation from the beginning can play an important role in addressing persistent societal problems in a credible, transparent, and multi-perspective way [2], as well as enable innovations [3]. Public decision making on sustainability is characterized by uncertainty, different values and interests, communities in dispute, as well as urgency [4], so that holistic approaches have included multiple fields of knowledge and perspectives of different stakeholders [5].

How is stakeholder participation used to contribute to a sustainable bioeconomy?

Most of the policy strategy developments in the bioeconomy have already adopted a more or less participatory approach, using stakeholder conferences, workshops and surveys [6] , and private–public partnerships to encourage successful market integration [7]. Poor coherence between decision makers, scientists, and stakeholders was assessed to be at the origin of regulatory failures [8], and biotechnology was the subject of controversial public debates, making societal acceptance an enabling factor [9].

Bioeconomy policy based on a broad societal debate should be a democratic imperative, and NGOs, as important public-opinion formers, have to participate [10]. Thus, the new European Bioeconomy Strategy explicitly calls for strategic and systematic approaches to bringing all stakeholders together in an attempt at policy coherence [11]. Therefore, researchers, initiatives, NGOs, and market actors have to be linked more closely with multi-lateral policy processes and intergovernmental discussions [12], far beyond the traditional “triple helix” concepts (public sector, academia, business) or “fig leaf” participation, and should be mobilized by a common vision of a sustainable bioeconomy system. Otherwise, stakeholders with specific interests may dominate these developments and not necessarily contribute to the public good [13]. Overall, the relationships between social, economic and ecological aspects (synergies, trade-offs, contradictions) characterize not only the interpretation of sustainability in general, but are also very relevant towards monitoring and further discussion regarding the development of the bioeconomy. Participation becomes particularly important when, as in Germany and the bioeconomy discourse in recent years, socio-ecological conflicts intensify and discussions, attitudes and mentalities become increasingly polarized [14].

Altogether, continuous stakeholder involvement supports the societal discourse and forming of opinions on the bioeconomy as well as contributes to a “learning” monitoring (reflective, inclusive and adapted according to societal priorities and needs). Key parameters and dimension can be identified to further develop the monitoring (aspects to be more or less considered in detail) to improve overall acceptance and consistency.

What are the limitations?

The outcome and conclusions gained from different forms of stakeholder participation critically depend on the representativeness of the participants. This can be a particular challenge when a certain level of knowledge is a prerequisite for participation, or when e.g. specific interests provide higher levels of motivation to participate.

Summary of key results: How stakeholder participation improves bioeconomy monitoring

Stakeholder expectations of a bioeconomy monitoring in Germany were assessed in stakeholder workshops in 2017 [15]. The stakeholders from science and society showed more universal interests than business stakeholders, which follow particular interests when it comes to the relevance of different SDGs for bioeconomy monitoring (See the figure below) [15]. A strong influence of changing discourses and narratives affecting policy processes and public opinions could be observed, as well as a growing awareness of global shifts and big societal challenges, e.g. hunger, poverty, and inequality. After the elimination of hunger, which seems more relevant for other countries, stakeholders put particular emphasis to SDGs 12, 15, 14, 6 and 13.

Analysis of German stakeholder group perspectives on SDGs regarding the bioeconomy, relevance of SDGs based on relevance of corresponding subgoals given by stakeholder groups. (Source: Zeug et al. (2019) [15], pp.9)

In January 2020, a further stakeholder workshop served to develop and underline the conceptual framework of the bioeconomy monitoring and its indicators, or to question it (see the figure below). The monitoring served as the basis for the discussion of conflicting goals and environmental problems. Within politics, the monitoring primarily should fulfill the function of evaluating the national bioeconomy strategy and its implementation. Within science, monitoring can help to forecast the future of bioeconomy, to record trends and to create scenarios. However, only with an informed public discourse, can the development of the bioeconomy lead to a societal change that favors the achievement of a sustainable bioeconomy. The limits of the bioeconomy should be shown by means of the monitoring. According to the participant stakeholders, the bioeconomy monitoring should be continuous and contribute to developing possible future visions of the bioeconomy. Developing future visions and narratives of a sustainable bioeconomy, knowledge transfer and discourse towards societal change were evaluated as major challenges in the future.

Clustered feedback from stakeholders in the SYMOBIO workshop 2020 (Source: Zeug et al. (2021) [16], pp.2)

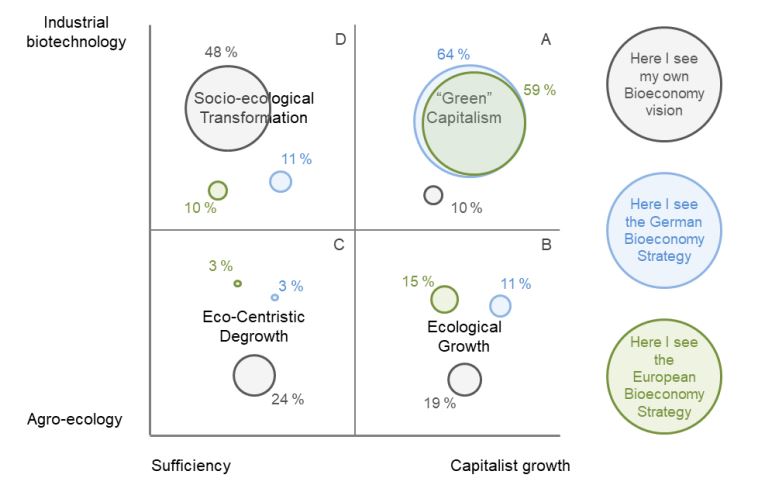

Stakeholders also evaluated the pilot report through a survey. Stakeholders considered the report and results as in general acceptable (3.2/5.0), however social impacts were shown to be perceived as underrepresented (2.4/5.0) and the socio-economic view to narrow, e.g. working conditions, inequalities, sustainable consumption & production were highlighted as missing [16]. The stakeholders also saw the need for the bioeconomy to be part of a socio-ecological transformation, beyond business-as usual (see also [17]), claiming global responsibility and providing a good life for all within planetary boundaries.

Shares of responses to the questions "Where do you see your own bioeconomy vision?", “Where do you see the German Bioeconomy Strategy?”, “Where do you see the European Bioeconomy Strategy?” (Source: Zeug et al. (2021) [16], pp.9).

Notes and references

- See the following sources from more information:

- Eversberg and Fritz (2022). Bioeconomy as a societal transformation: Mentalities, conflicts and social practices. Product. and Consum. doi: 10.1016/j.spc.2022.01.021.

- Eversberg (2021). The Social Specificity of Societal Nature Relations in a Flexible Capitalist Society. Val. doi: 10.3197/096327120X15916910310581.

- Eversberg and Holz (2020). Empty Promises of Growth: The Bioeconomy and Its Multiple Reality Checks. Available at: https://www.flumen.uni-jena.de/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/Working-Paper-Nr.-2_Eversberg-Holz_Empty-Promises-of-Growth-The-Bioeconomy-and-Its-Multiple-Reality-Checks-1.pdf.

- Hausknost et al. (2017). A Transition to Which Bioeconomy? An Exploration of Diverging Techno-Political Choices. doi: 10.3390/su9040669.

- Zeug et al. (2022). Life Cycle Sustainability Assessment for Sustainable Bioeconomy, Societal-Ecological Transformation and Beyond. Progress in LCA. Sustainable Production, Life Cycle Engineering and Management. Springer.

- Bezama (2018). Understanding the systems that characterise the circular economy and the bioeconomy. Waste Management & Research. doi: 10.1177/0734242X18787954 and Gerdes et al. (2018). Engaging stakeholders and citizens in the bioeconomy: Lessons learned from BioSTEP and recommendations for future research. Available at: https://www.ecologic.eu/sites/default/files/publication/2018/2801-biostep_d4.2_lessons_learned_from_biostep.pdfm.

- Kircher et al. (2018). How to capture the bioeconomy’s industrial and regional potential through professional cluster management. New Biotechn. doi: 10.1016/j.nbt.2017.05.007.

- See:

- Funtowicz and Ravetz (1990). Uncertainty and Quality in Science for Policy. doi: 10.1007/978-94-009-0621-1_3.

- Martinez-Alier et al. (1998). Weak comparability of values as a foundation for ecological economics. Econ. doi: 10.1016/S0921-8009(97)00120-1.

- Munda (2008). Social Multi-Criteria Evaluation for a Sustainable Economy.

- Garmendia and Gamboa (2012). Weighting social preferences in participatory multi-criteria evaluations: A case study on sustainable natural resource management. Ecol. Econ. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2012.09.004 and O'Neill (2001). Representing people, representing nature, representing the world. Environ. and Plan. C-Governm. and Policy. doi: 10.1068/c12s.

- German Bioeconomy Council (2018). Update Report of National Strategies around the World - Bioeconomy Policy (Part III). Available at: https://www.iwbio.de/user/pages/04.publikationen/bioeconomy-policy-part-iii-update-report-of-national-strategies-around-the-world/GBS_2018_Bioeconomy-Strategies-around-the_World_Part-III.pdf.

- de Besi and McCormick (2015). Towards a Bioeconomy in Europe: National, Regional and Industrial Strategies. Sustain. doi: 10.3390/su70810461.

- European Commission (2012). Innovating for Sustainable Growth: A Bioeconomy for Europe. Available at: https://www.ecsite.eu/sites/default/files/201202_innovating_sustainable_growth_en.pdf.

- Małyska and Jacobi (2018). Plant breeding as the cornerstone of a sustainable bioeconomy. New Biotechn. doi: 10.1016/j.nbt.2017.06.011.

- Civil Society Action-Forum on Bioeconomy (2019). Declaration of German Environmental and Development Organizations on the Bioeconomy Policy of the Federal Government of Germany. Available at: https://denkhausbremen.de/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/German-ENGO-Bioeconomy-declaration-.pdf.

- EC (2018). A sustainable bioeconomy for Europe: strengthening the connection between economy, society and the environment. Available at: https://eagri.cz/public/web/file/600668/bioeconomy_strategy_2018.pdf.

- See:

- Ingrao et al. (2018). The potential roles of bio-economy in the transition to equitable, sustainable, post fossil-carbon societies: Findings from this virtual special issue. Journal of Clean. Produ. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.09.068.

- El-Chichakli et al. (2016). Policy: Five cornerstones of a global bioeconomy. Nat. doi: 10.1038/535221a.

- Nilsson and Costanza (2015). Overall Framework for the Sustainable Development Goal Review of Targets for the Sustainable Development Goals: The Science Perspective. Available at: http://scholar.ceu.edu/sites/default/files/publications/sdg-report.pdf#page=9.

- Lubchenco et al. (2015). Sustainability rooted in science. Geoscien. doi: 10.1038/ngeo2552.

- Pfau et al. (2014). Visions of Sustainability in Bioeconomy Research. Sustain. doi: 10.3390/su6031222

- Eversberg (2020). Bioökonomie als Einsatz polarisierter sozialer Konflikte? Zur Verteilung sozial-ökologischer Mentalitäten in der deutschen Bevölkerung 2018 und möglichen Unterstützungs- und Widerstandspotentialen gegenüber bio-basierten Transformationen. Available at: https://www.db-thueringen.de/servlets/MCRFileNodeServlet/dbt_derivate_00053605/WorkingPaper_Flumen_001.pdf.

Eversberg and Fritz (2022). Bioeconomy as a societal transformation: Mentalities, conflicts and social practices. Sustain. Product. and Consum. doi: 10.1016/j.spc.2022.01.021. - Zeug et al. (2019). Stakeholders’ Interests and Perceptions of Bioeconomy Monitoring Using a Sustainable Development Goal Framework. Sustain. doi: 10.3390/su11061511.

- Zeug et al. (2021). Results from a Stakeholder Survey on Bioeconomy Monitoring and Perceptions on Bioeconomy in Germany. UFZ Discus. Pap. Available at: https://www.econstor.eu/bitstream/10419/248425/1/1780993706.pdf.

- Eversberg and Holz (2020). Empty Promises of Growth: The Bioeconomy and Its Multiple Reality Checks. Available at: https://www.flumen.uni-jena.de/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/Working-Paper-Nr.-2_Eversberg-Holz_Empty-Promises-of-Growth-The-Bioeconomy-and-Its-Multiple-Reality-Checks-1.pdf.